JEDDAH: Rami Farook’s solo exhibition ‘A Muslim Man,’ which runs at Jeddah’s ATHR Gallery until March 25, is a deeply personal sequel of sorts to a film he made in 2015, and traces the evolution of his life, identity and creative practice over the past decade.

The original project, a 64-minute conceptual feature comprising 16 vignettes, has now been reimagined as a labyrinth-like multimedia experience featuring 85 pieces, each of which is based on a scene from that film.

The self-taught Emirati artist was 20 in 2001 when he lost his best friend. Four months later, while living in the US, the events of 9/11 drastically altered his life. As a Muslim, Arab-looking man, he recalls: “I became noticed, vilified… it shifted everything.” These events inspired a deeper exploration of his faith and identity, themes that are central to this show.

“It’s about a Muslim man’s relationship with God, self, society and family,” he tells Arab News.

Following the events of Oct. 7, 2023, and the outbreak of genocidal violence in Palestine, Farook turned to painting as a coping mechanism. “I painted daily, summarizing the news,” he says. This renewed urgency also shaped the exhibition’s tone. The ‘Muslim Man’ is portrayed as both a victim and a hero.

Farook describes the show as “an immersive, intermedia experience.” It is his first attempt at blending multiple mediums into one cohesive journey. “For me, this was a fun curatorial process, way more magical than just watching the film,” he says.

The “docufictional” exhibition is structured like a film, however, and unfolds across seven sections: context, protagonist, cause of conflict, conflict, response to conflict, climax, and moral, Farook explains.

Here, he talks us through several works from the show.

‘Aerial View’

This is the poster for the show; the reason I like it as the poster is you can look at it in any of the seven sections I mentioned earlier — context, protagonist, cause of conflict, conflict, response to conflict, climax, and moral — and it could be in any of them. The character is a Muslim man. This shot presents him as a hero — because we’ve seen the villain side too many times in the last 25 years or more. This show is showing the other side. He’s on a ladder that looks like it’s not in the greatest shape. The village he’s looking at: is it alive? Is it dead? There’s the mystery. And whether he is looking to see what’s going on to eventually maybe protect it, we don’t know. So there’s a lot of mystery.

‘Caring for His Father’

This is a closeup of me holding my dad’s hand. He wears white, I wear black. My dad cannot see; he lost around 50 percent of his eyesight in the last 40 years, and then he lost another maybe 40 percent in the last four or five years. He just sees light at this point. So, I care for him, especially recently. And I just felt like I wanted it to be here. This exhibition is docufictional — it can be about me, but it’s also general.

‘Alone’

I made a mattress that’s exactly my height, my width and my depth. It literally just fits me. It’s the idea that rest, contemplation… it all happens lying down in bed. Later, I thought it also kind of looks like a casket. Originally, it was going to have a fitted sheet or a cover, and a pillow; I made a pillow that’s just the size of my head. I try to strip things down as much as possible to just the absolute basics. Maybe I’ll add it later. This is a living exhibition; I wouldn’t be surprised if I end up adding things later — there are some things here that weren’t planned.

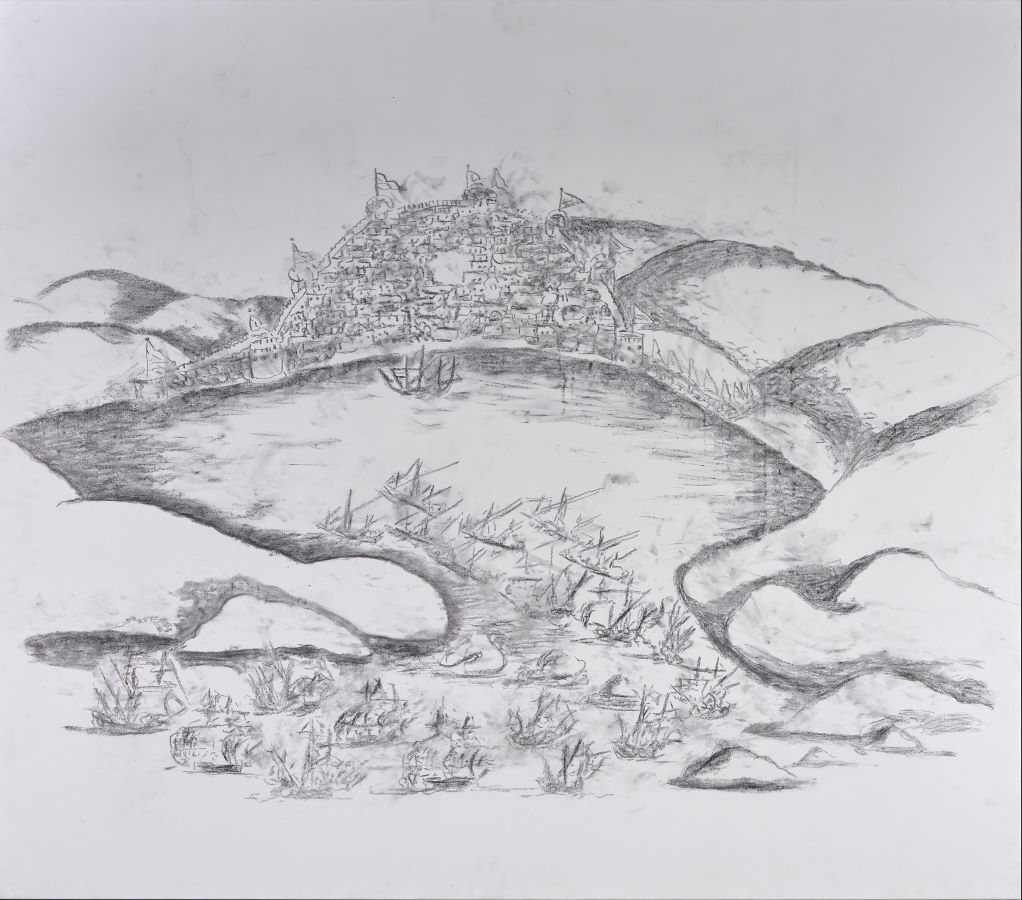

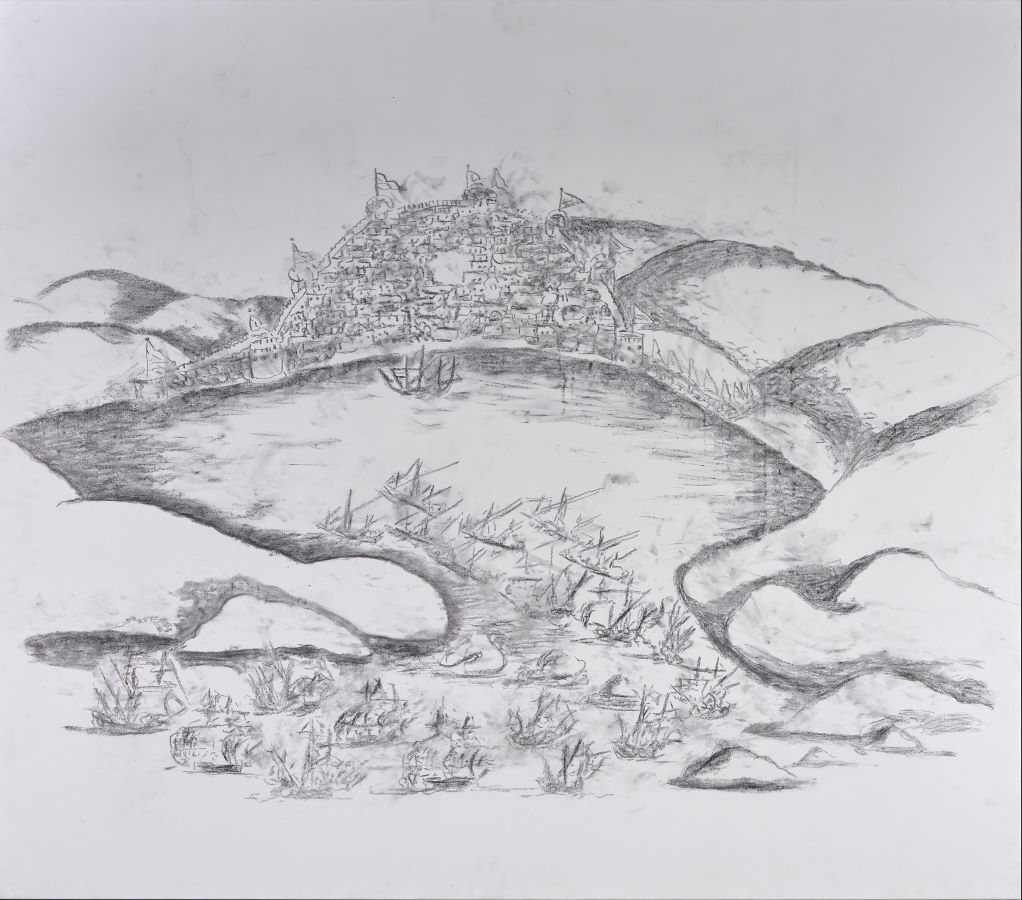

‘The Siege of Jeddah/A Determined Defense’

This captures the moment the Portuguese tried to invade Jeddah. The commander at the time, they put up a determined defense for about 30 to 35 days. It’s significant to showcase it here because there’s only two works in the show that are Jeddah-specific. So for me, it’s beautiful. Jeddah is a city that I love very much. It makes you wonder, if the Portuguese did occupy Jeddah, how everything would be different now.

‘Allah So Determined And Did As He Willed’

This, honestly, is a (phrase) that is my cure to any worry. We all look back at our lives — especially at the big things that we invested time, money, or whatever, into, and we could always ask: how could we guarantee that things — business, relationships, or anything — would have been better if we changed something? This phrase actually helps me to not live with regrets.