LONDON: Amid sweeping foreign aid cuts, Afghanistan’s healthcare system has been left teetering on the brink of collapse, with 80 percent of World Health Organization-supported services projected to shut down by June, threatening critical medical access for millions.

The abrupt closure of the US Agency for International Development, which once provided more than 40 percent of all humanitarian assistance to the impoverished nation of 40 million, dealt a devastating blow to an already fragile health system.

Supporters of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) rally outside the US Capitol on February 05, 2025 in Washington, DC, to protest the Trump Administration's sudden closure of the agency. (AFP)

Researcher and public health expert Dr. Shafiq Mirzazada said that while it was too early to declare Afghanistan’s health system was in a state of collapse, the consequences of the aid cuts would be severe for “the entire population.”

“WHO funding is only one part of the system,” he told Arab News, pointing out that Afghanistan’s health sector is fully funded by donors through the Afghanistan Resilience Trust Fund, known as the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund before August 2021.

Established in 2002 after the US-led invasion, the ARTF supports international development in Afghanistan. Since the Taliban retook Kabul in August 2021, the fund has focused on providing essential services through UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations

Funding shortages resulting from foreign aid cuts have already forced scores of health facilities across Afghanistan to reduce services or close altogether, with the most vulnerable bearing the brunt, according to the WHO. (AFP file)

However, this approach has struggled to meet the growing needs, as donor fatigue and political challenges compound funding shortages.

“A significant portion of the funding goes to health programs through UNICEF and WHO,” Mirzazada said, referring to the UN children’s fund. “Primarily UNICEF channels funds through the Health Emergency Response project.”

Yet even those efforts have proven insufficient as facilities close at an alarming rate.

By early March, funding shortages forced 167 health facilities to close across 25 provinces, depriving 1.6 million people of care, according to the WHO.

Without urgent intervention, experts say 220 more facilities could close by June, leaving a further 1.8 million Afghans without primary care — particularly in northern, western and northeastern regions.

The closures are not just logistical setbacks, they represent life-or-death outcomes for millions.

“The consequences will be measured in lives lost,” Edwin Ceniza Salvador, the WHO’s representative in Afghanistan, said in a statement.

Dr. Edwin Ceniza Salvador, World Health Organization's representative in Afghanistan. (Supplied)

“These closures are not just numbers on a report. They represent mothers unable to give birth safely, children missing lifesaving vaccinations, entire communities left without protection from deadly disease outbreaks.”

Bearing the brunt of Afghanistan’s healthcare crisis are the most vulnerable populations, including pregnant women, children in need of vaccinations and those living in overcrowded displacement camps, where they are exposed to infectious and vaccine-preventable diseases.

This photograph taken on January 9, 2024 shows Afghan women and children refugees deported from Pakistan, in a nutrition ward at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees camp on the outskirts of Kabul. (AFP)

Because Afghanistan’s health system was heavily focused on maternal and child care, Mirzazada said: “Any disruption will primarily affect women and children — including, but not limited to, vaccine-preventable diseases, as well as antenatal, delivery and postnatal services.

“We’re already seeing challenges, with outbreaks of measles in the country. The number of deaths due to measles is rising.”

This trend will be exacerbated by declining immunization rates.

A health worker administers polio vaccine drops to a child during a vaccination campaign in the old quarters of Kabul on November 8, 2021. (AFP)

“Children will face more diseases as vaccine coverage continues to decline,” Mirzazada said.

“We can already see a reduction in vaccine coverage. The Afghanistan Health Survey 2018 showed basic vaccine coverage at 51.4 percent, while the recent UNICEF-led Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey shows it has dropped to 36.6 percent in 2022-23.”

IN NUMBERS:

• 14.3 million Afghans in need of medical assistance

• $126.7 million Funding needed for healthcare

• 22.9 million Afghans requiring urgent aid to access healthcare, food and clean water.

The WHO recorded more than 16,000 suspected measles cases, including 111 deaths, in the first two months of 2025 alone.

It warned that with immunization rates critically low — 51 percent for the first dose of the measles vaccine and 37 percent for the second — children were at heightened risk of preventable illness and death.

Meanwhile, midwives have reported dire conditions in the nation’s remaining facilities. Women in labor are arriving too late for lifesaving interventions due to clinic closures.

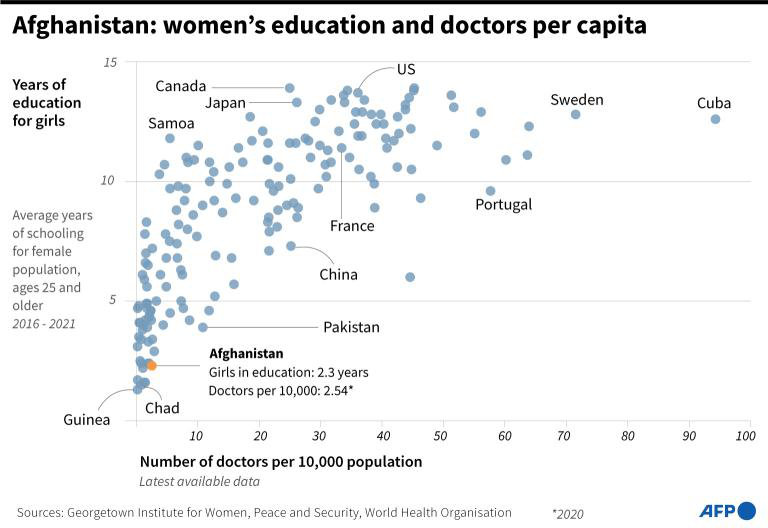

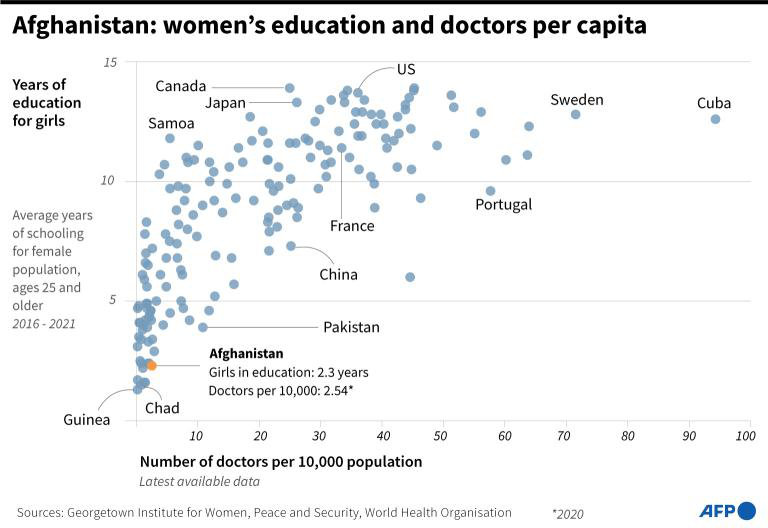

Women and girls are disproportionately bearing the brunt of these health challenges in great part due to Taliban policies.

Restrictions on women’s freedom of movement and employment have severely limited health access, while bans on education for women and girls have all but eliminated training for future female health workers.

In December, the Taliban closed all midwifery and nursing schools.

Wahid Majrooh, founder of the Afghanistan Center for Health and Peace Studies, said the move “threatens the capacity of Afghanistan’s already fragile health system” and violated international human rights commitments.

He wrote in the Lancet Global Health journal that “if left unaddressed, this restriction could set precedence for other fragile settings in which women’s rights are compromised.”

This picture taken on October 6, 2021 shows a midwife (L) and a nutrition counsellor weighing a baby at the Tangi Saidan clinic run by the Swedish Committee for Afghanistan, in Daymirdad district of Wardak province. (AFP file)

“Afghanistan faces a multifaceted crisis marked by alarming rates of poverty, human rights violations, economic instability and political deadlock, predominantly affecting women and children,” the former Afghan health minister said.

“Women are denied their basic rights to education, work and, to a large extent, access to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The ban on midwifery schools limits women’s access to health, erodes their agency in health institutions and eradicates women role models.”

Majrooh described the ban on midwifery and nursing education as “a public health emergency” that “requires urgent action.”

Afghanistan is facing one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises, with 22.9 million people — roughly half its population — requiring urgent aid to access healthcare, food and clean water.

Critical funding shortfalls and operational barriers now jeopardize support for 3.5 million children aged 6 to 59 months facing acute malnutrition, according to UN figures, as aid groups grapple with the intersecting challenges of economic collapse, climate shocks and Taliban restrictions.

The provinces of Kabul, Helmand, Nangarhar, Herat and Kandahar bear the heaviest burden, collectively accounting for 42 percent of the nation’s malnutrition cases. As a result, aid organizations are struggling to meet the needs of malnourished children, with recent cuts in foreign aid forcing Save the Children to suspend lifesaving programs.

As vaccine coverage continues to decline, children will be the most vulnerable to diseases. (ARTF photo)

The UK-based charity has closed 18 health facilities and faces the potential closure of 14 more unless new funding is secured. These 32 clinics provided critical care to 134,000 children in January alone, including therapeutic feeding and immunizations, it said in a statement.

“With more children in need of aid than ever before, cutting off lifesaving support now is like trying to extinguish a wildfire with a hose that’s running out of water,” Gabriella Waaijman, chief operating officer at Save the Children International, said.

As well as the hunger crisis, Afghanistan is battling outbreaks of malaria, measles, dengue, polio and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. The WHO said that without functioning health facilities, efforts to control these diseases would be severely hindered.

Afghan refugees along with their belongings arrive on trucks from Pakistan, near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border in the Spin Boldak district of Kandahar province on November 20, 2023. (AFP)

The risk may be higher among internally displaced communities. Four decades of conflict have driven repeated waves of forced displacement, both within Afghanistan and across its borders, while recurring natural disasters have worsened the crisis.

About 6.3 million people remain displaced within the country, living in precarious conditions without access to adequate shelter or essential services, according to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR.

Mass deportations have compounded the crisis. More than 1.2 million Afghans returning from neighboring countries such as Pakistan in 2024 are now crowded into makeshift camps with poor sanitation. This had fueled outbreaks of measles, acute watery diarrhea, dengue fever and malaria, the UNHCR said in October.

Afghan refugees along with their belongings sit beside the trucks at a registration centre, upon their arrival from Pakistan in Takhta Pul district of Kandahar province on Dec. 18, 2023. (AFP)

With limited healthcare access, other diseases are also spreading rapidly.

Respiratory infections and COVID-19 are surging among returnees, with 293 suspected cases detected at border crossings in early 2025, according to the WHO’s February Emergency Situation Report.

Cases of acute respiratory infections, including pneumonia, have also risen, with 54 cases reported, primarily in children under the age of 5.

Afghan boys sit with their winter kits from UNICEF at Fayzabad in Badakhshan province on February 25, 2024. (AFP)

The WHO said that returnees settling in remote areas faced “healthcare deserts,” where clinics had been shuttered for years and where there were no aid pipelines.

Water scarcity in 30 provinces exacerbates acute watery diarrhea risks, while explosive ordnance contamination and road accidents cause trauma cases that overwhelm understaffed facilities.

This photo taken on July 21, 2022 shows people outside the Boost Hospital, run by Medicines Sans Frontiers (MSF), in Lashkar Gah, Helmand. (AFP)

Mirzazada said that “while the ARTF has some funds, they won’t be enough to sustain the system long term.”

To prevent the collapse of Afghanistan’s health system and keep services running, he urged the country’s Taliban authorities to contribute to its funding.

“Government contributions have been very limited in the past and now even more so,” he said.

In this photo taken on June 3, 2021, Qari Hafizullah Hamdan (2nd L), health official for the Qarabagh district, visits patients at a hospital in the Andar district of Ghazni province. Taliban authorities had been urged to contribute to the ARTF to prevent a collapse of the country's health care system. (AFP File)

“However, the recently developed health policy for Afghanistan mentions internally sourced funding for the health system. If that happens under the current or future authorities, it could help prevent collapse.”

He also called on Islamic and Arab nations to increase their funding efforts.

“Historically, Western countries have been the main funders of the ARTF,” Mirzazada said. “The largest contributors were the US, Germany, the European Commission and other Western nations.

“Islamic and Arab countries have contributed very little. That could change and still be channeled through the UN system, as NGOs continue to deliver services on behalf of donors and the government.

“This approach could remain in place until a solid, internally funded health system is established.”