NABEK, Syria: In a centuries-old monastery on a rocky hill north of Damascus, friends of missing Italian priest Paolo Dall’Oglio carry on his legacy, hopeful Bashar Assad’s ouster might help reveal the Jesuit’s fate.

“We want to know if Father Paolo is alive or dead, who imprisoned him, and what was his fate,” said Father Jihad Youssef who heads Deir Mar Musa Al-Habashi, about 100 kilometers (62 miles) north of Damascus.

For years, Dall’Oglio lived in Deir Mar Musa — the monastery of St. Moses the Ethiopian — which dates to around the 6th century. He is credited with helping restore the place of worship.

A fierce critic of Assad, whose 2011 repression of anti-government protests sparked war, he was exiled the following year for meeting with opposition members, returning secretly to opposition-controlled areas in 2013.

He disappeared that summer while heading to the Raqqa headquarters of a group that would later become known as the Daesh, to plead for the release of kidnapped activists.

Conflicting reports emerged on Dall’Oglio’s whereabouts, including that he was kidnapped by the extremists, killed or handed to the Syrian government.

Daesh’s territorial defeat in Syria in 2019 brought no new information.

Tens of thousands of people have been detained or gone missing in Syria during more than a decade of conflict, many disappearing into Assad’s jails.

His December overthrow has enabled his friends at the monastery to openly discuss suspicions Dall’Oglio might have been “imprisoned by the regime,” Youssef said.

“We waited to see a sign of him... in Saydnaya prison or Palestine Branch,” Youssef said, referring to notorious detention facilities from which detainees were released after Assad’s toppling.

“We were told a lot of things, including that he was seen in the Adra prison in 2019,” Youssef said, referring to another facility outside Damascus, “but nothing reliable.”

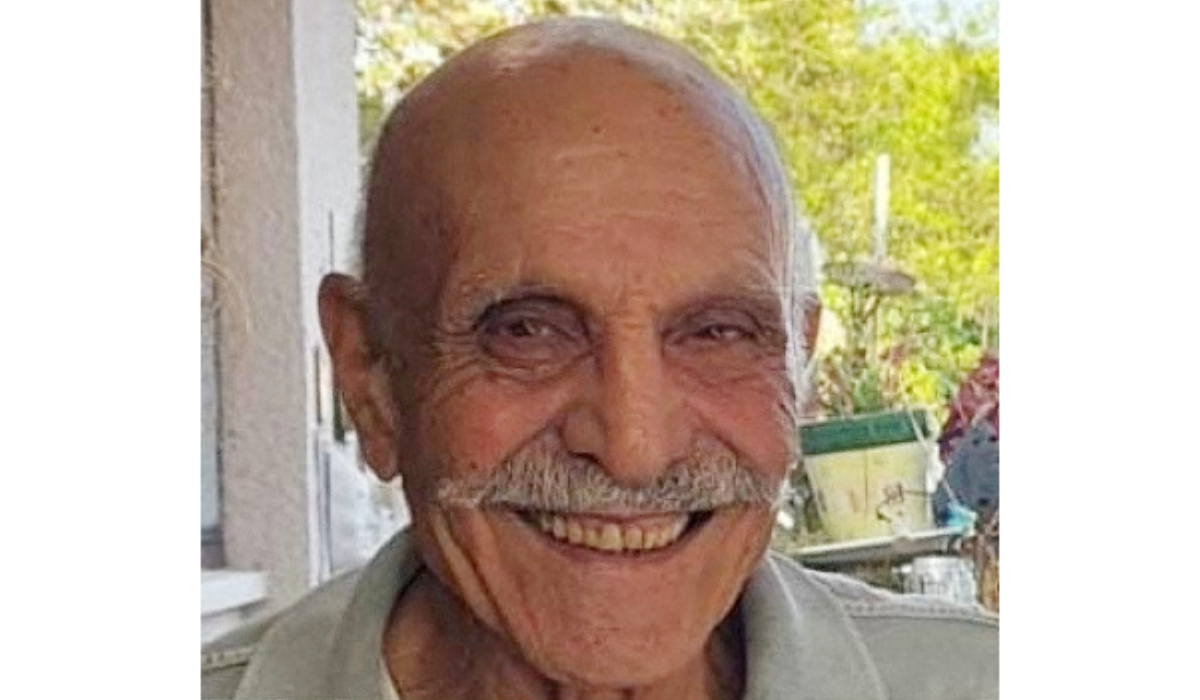

Dall’Oglio, born in 1954, hosted interfaith seminars at Deir Mar Musa where Syria’s Christian minority and Muslims used to pray side by side, turning the monastery into a symbol of coexistence.

Youssef said it became a bridge for dialogue between Syrians in a country that “the former regime divided into sects who feared each other.”

Some 30,000 people visited in 2010, but the war and Dall’Oglio’s disappearance scared them away for more than a decade.

The monastery reopened for visitors in 2022.

“I didn’t know Father Paolo,” said Shatha Al-Barrah, 28, who came to Deir Mar Musa seeking solace and reflection.

But “I know he reflects this monastery, which opens its heart to all people from all faiths,” said the interpreter as she climbed the 300 steps leading to the building, built on the ruins of a Roman tower and partly carved into the rock.

Julian Zakka said Dall’Oglio was one of the reasons he joined the Jesuit order.

“Father Paolo used to work against associating Islam with extremists,” said the 28-year-old, “and to emphasize that coexistence is possible.”

After Islamist-led rebels ended half a century of one-family rule, the new authorities have sought to reassure minorities that they will be protected.

Assad had presented himself as a protector of minorities in multi-ethnic, multi-confessional Syria, but largely concentrated power in the hands of the Alawite community to whom his family belonged.

This month, Jesuits in Syria emphasized the need for healing, noting in a statement that fear had “shackled” the community for years.

Youssef said that while “the regime presented itself as protecting us, in fact it was using us as protection.”

He expressed optimism that “at last, the load has been lifted from our chests and we can breathe” after decades of “political death,” adding that he hoped the new authorities would be inclusive.

For now, Youssef is intent on spreading Dall’Oglio’s message.

“We will return to organizing activities like he loved to do,” Youssef said, including a march in Homs province, home to Alawites, Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

“The regime caused deep wounds between the Islamic sects” in Homs, he said.

“Father Paolo wanted to organize a large procession there — to pray at the mass graves, to be a bridge between people — to let them listen to each other’s pain, grieve and cry together, and stand hand in hand.”