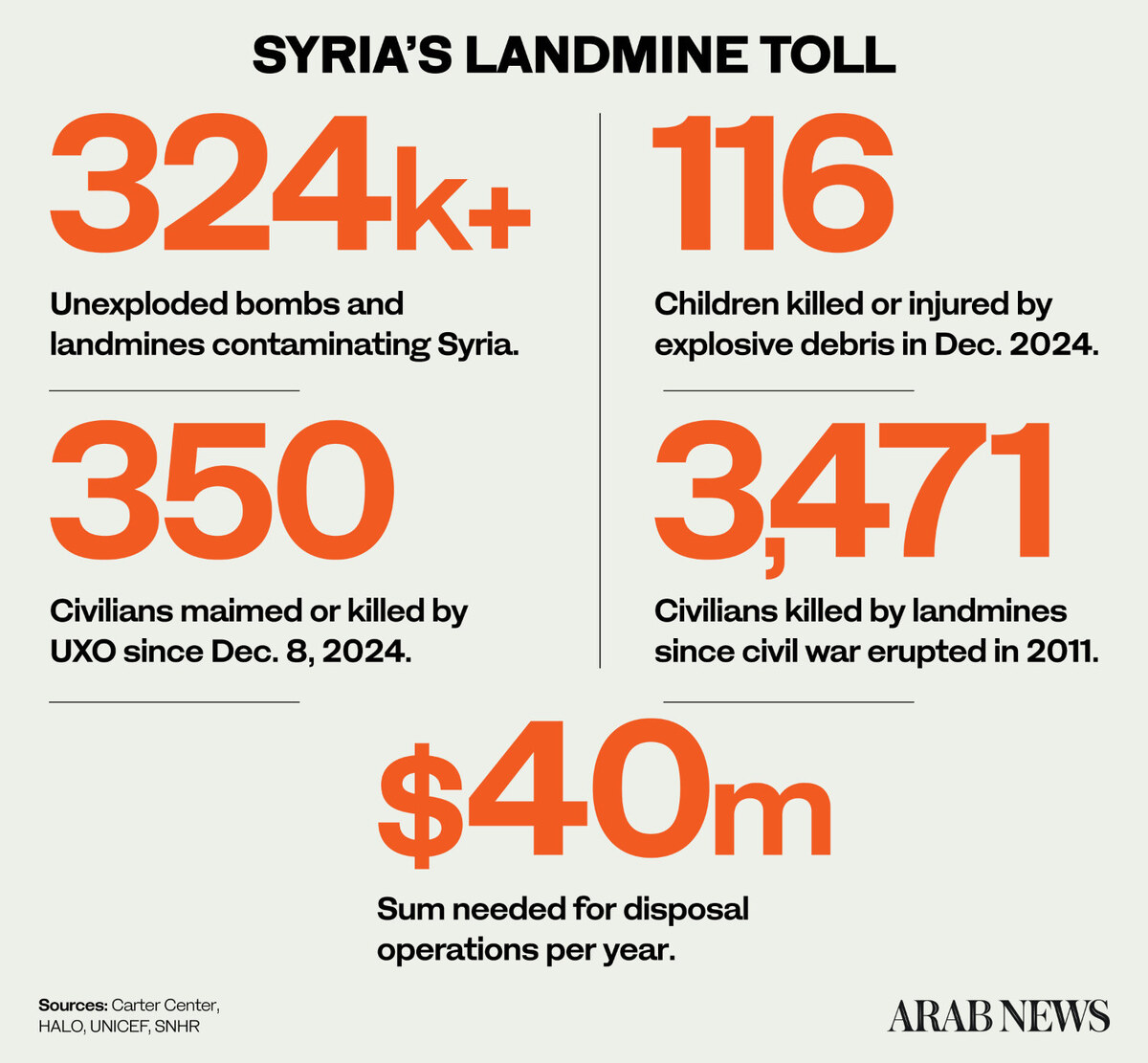

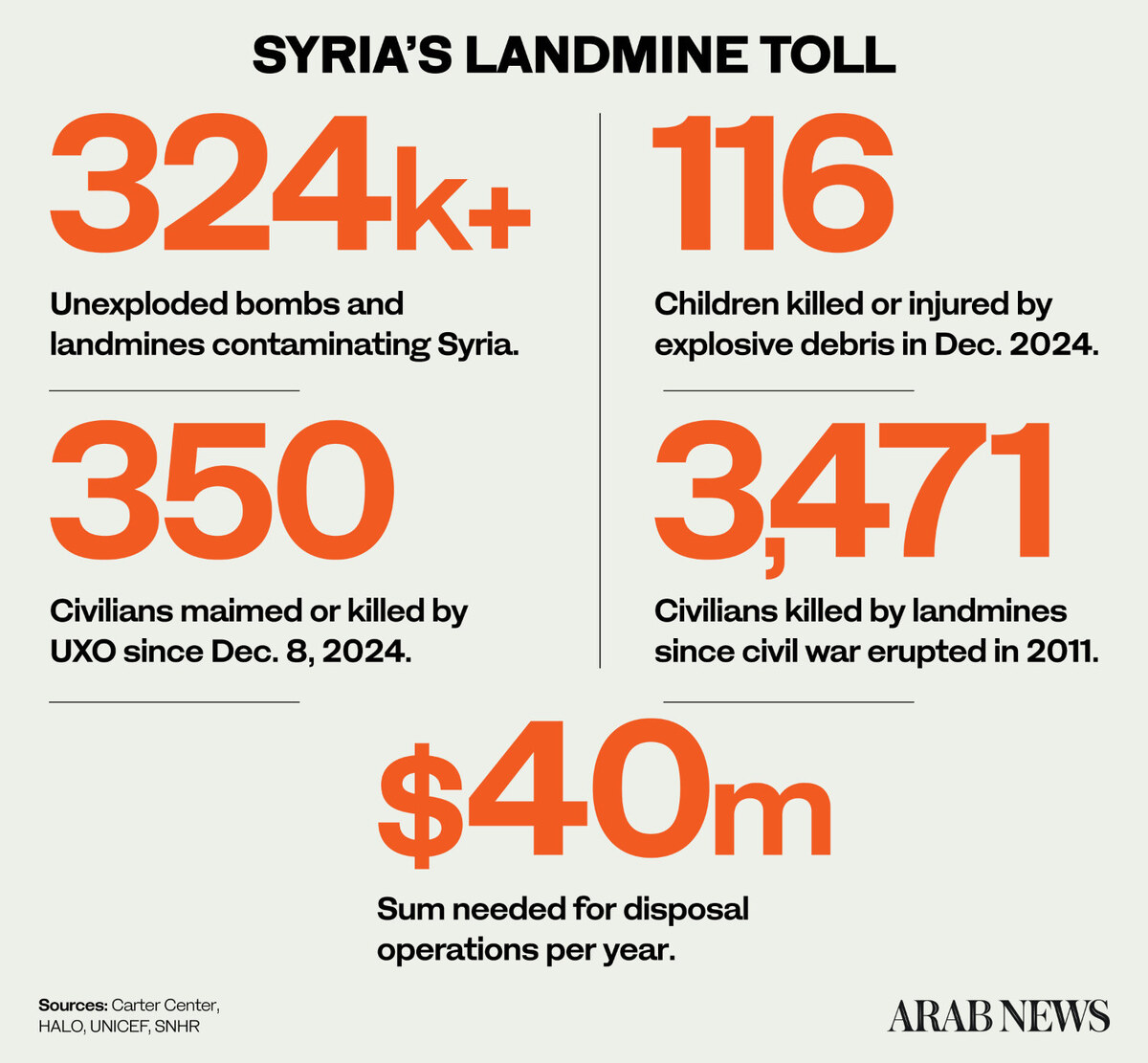

INNUMBERS

* 324,600+ Unexploded bombs and landmines contaminating Syrian Arab Republic.

* 350 Civilians maimed or killed by UXO in Syrian Arab Republic since Dec. 8, 2024.

* 116 Children killed or injured by explosive debris in Syrian Arab Republic in December 2024.

* 3,471 Civilians killed by landmines in Syrian Arab Republic since 2011.

*$40m Funds needed by Syrian Arab Republic for disposal operations per year.

Sources: Carter Center, HALO, UNICEF, SNHR

ANAN TELLO

LONDON: The sudden fall of Bashar Assad’s regime in early December prompted around 200,000 Syrians to return to their war-ravaged homeland, despite the widespread devastation. But the land they have come to reclaim harbors a deadly threat.

Almost 14 years of civil war contaminated swathes of the Syrian Arab Republic with roughly 324,600 unexploded rockets and bombs and thousands of landmines, according to a 2023 estimate by the US-based Carter Center.

In the last four years alone, the Syrian Arab Republic has recorded more casualties resulting from unexploded ordnance than any other country, yet no nationwide survey of minefields or former battlefields has been conducted, according to The HALO Trust.

Those explosives have maimed or killed at least 350 civilians across the Syrian Arab Republic since the Assad regime fell on Dec. 8, Paul McCann, a spokesperson for the Scotland-based landmine awareness and clearance charity, told Arab News.

The actual toll, however, is likely much higher. “We think that’s an undercount because large areas of the country have no access or monitoring, particularly in the east,” he added.

Children bear the brunt of these hidden killers.

Ted Chaiban, deputy executive director for humanitarian action and supply operations at the UN children’s agency, UNICEF, warned that explosive debris is the leading cause of child casualties in Syria, killing or injuring at least 116 in December alone.

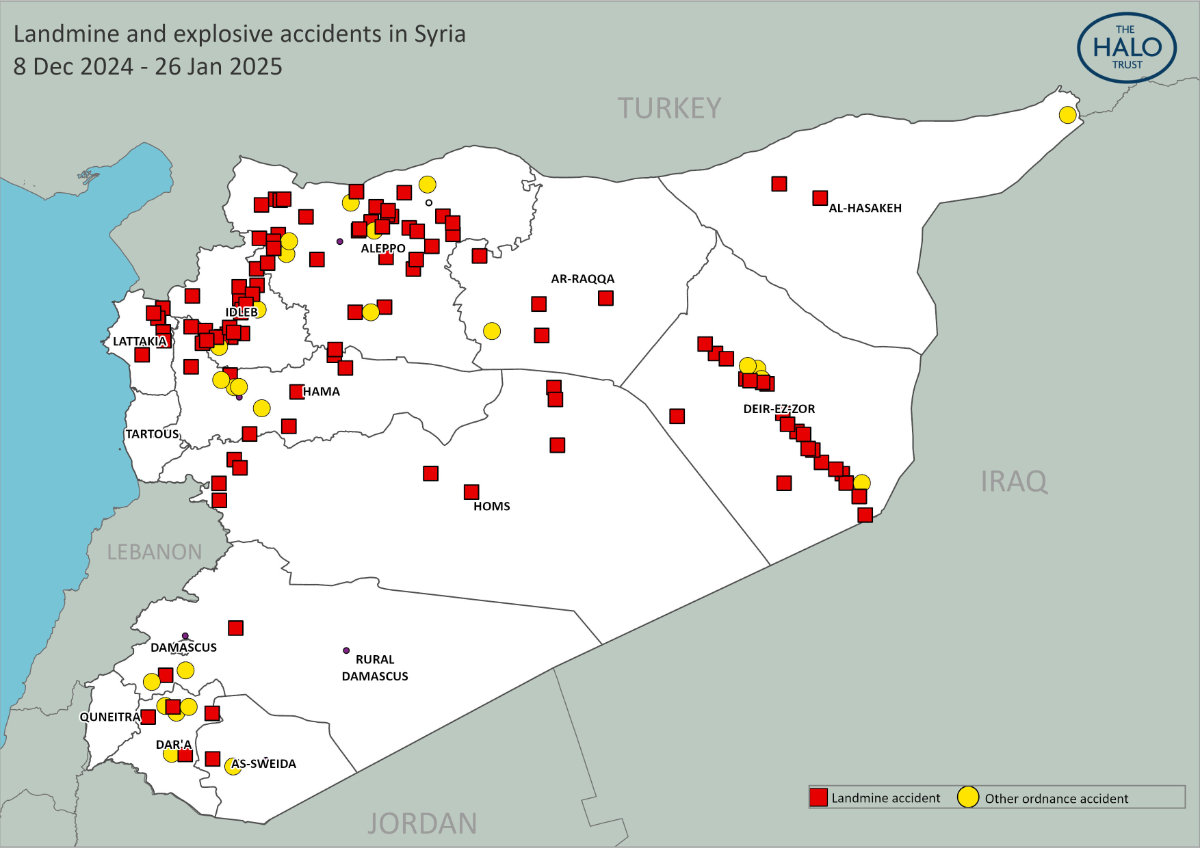

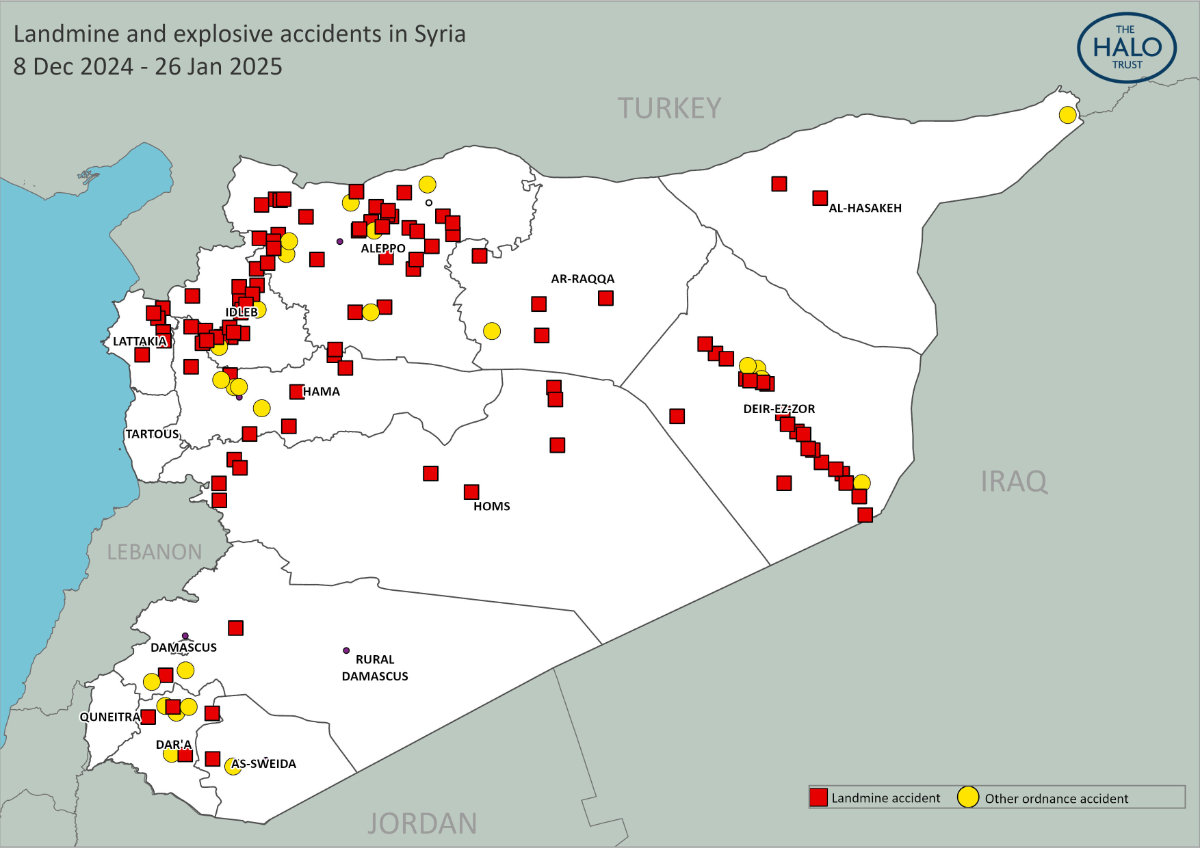

According to McCann, the bulk of the documented incidents involving landmines and unexploded ordnance took place in Idlib province, north of Aleppo, and Deir Ezzor, where intense battles between regime forces and opposition groups had occurred.

“There is a long frontline — maybe several hundred kilometers — running through parts of Latakia, Idlib, and up to north of Aleppo, where the government was on one side, and they built large earthen barriers,” he said.

“They used bulldozers to push up big walls and dig trenches, and in front of their military positions they put a lot of minefields.”

McCann said the exact number of landmines, across the Syrian Arab Republic and in the northwest specifically, remains unknown. “We don’t know exactly how many, because there hasn’t been a national survey,” he said.

After the regime’s forces withdrew from these areas, locals discovered maps detailing the location of dozens of minefields. Although it will take time and resources to clear these explosives, such maps make containment far easier.

“There was a battalion command post, and when the troops left, local residents went in and found some maps of local minefields,” McCann said. “So, for that one area, we’ve discovered there were 40 minefields, but this could be repeated up and down this line for all the different military positions.”

Landmines planted systemically by warring parties are not the only threat. HALO reported “huge amounts of explosive contamination anywhere that there might have been a battle or been any kind of fighting.”

One such area is Saraqib, east of Idlib. The northwestern city endured a major battle in 2013, fell to rebel forces, was recaptured by the Syrian Army in 2020, and was then seized during the Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham-led offensive on Nov. 30.

“The city was fought over by the government and multiple different opposition groups, who sometimes fought each other,” McCann said. “And in a big spread south of there, there are dozens of villages that we’ve been through which are contaminated with explosives.”

The Carter Center warned in a report published in February 2024 that the “scale of the problem is so large that there is no way any single actor can address it.”

Since Assad’s ouster, HALO has seen a 10-fold surge in calls to its emergency hotline in areas near the Turkish border where it operates.

“Every time our teams dispose of a piece of ordnance… people hear the explosion and they come running to say, ‘I found something in my house’ or ‘I found something on my land, can you come and have a look? Can you come and take care of that?” McCann said.

“We are hoping to be able to increase the size of the program as quickly as possible to deal with the demand.”

As the only mine clearance operator in northwest Syria, HALO is struggling to keep up with surging demand. With funding for only 40 deminers, the organization is desperately understaffed, HALO’s Syrian Arab Republic program manager Damian O’Brien said in a statement.

HALO urgently needs emergency funding “to help bring the Syrian people home to safety,” he said. “Clearing the debris of war is fundamental to getting the country back on its feet,” he added.

The urgency of clearing unexploded ordnance in Syria has grown as displaced communities, often unaware of those hidden dangers, rush to return home and rebuild their lives.

“One of the problems we’re finding is the people are coming back now,” McCann said. “They want to plant the land for spring. They want to start getting the land ready because they’re going to need the income to rebuild.

“Millions of homes have been either destroyed by fighting, or they’ve been destroyed by the regime that stripped out the windows and the doors and the roofs and the copper pipes and the wiring to sell for scrap.”

The war in the Syrian Arab Republic created one of the largest displacement crises in the world, with more than 13 million forcibly displaced, according to UN figures. With Assad’s fall, hundreds of thousands returned from internal displacement and neighboring countries.

And as host countries, including Turkiye, Lebanon and Jordan, push to repatriate Syrian refugees, UNICEF’s Chaiban warned in January that “safe return cannot be achieved without intensified humanitarian demining efforts.”

HALO’s O’Brien warned in December that “returning Syrians simply don’t know where the landmines are lying in wait. They are scattered across fields, villages and towns, so people are horribly vulnerable.”

He added: “I’ve never seen anything quite like it. Tens of thousands of people are passing through heavily mined areas on a daily basis, causing unnecessary fatal accidents.”

Unless addressed, these hidden killers will impact multiple generations of Syrians, causing the loss of countless lives and limbs long after the conflict has ended, the Carter Center warned.

Economic development will also be disrupted, particularly in urban reconstruction and agriculture. Environmental degradation is another concern. As munitions break down, they leach chemicals into the soil and groundwater.

But safely demining an area is costly and securing adequate funding has been a challenge. Mouiad Alnofaly, HALO’s senior operations officer in the Syrian Arab Republic, said disposal operations could cost $40 million per year.

Faced with these limitations, locals eager to cultivate their farmland are turning to unofficial solutions, hiring amateurs who are not trained to international standards, resulting in more casualties, McCann warned.

“People are returning and trying to plant, and so we’re hearing reports that they’re hiring ex-military personnel with metal detectors to do some sort of clearance of their land, but it’s not systematic or professional,” he said.

“I met a man a few days ago who said his neighbor had hired an ex-soldier with a metal detector to find the mines on his land. The man (ex-soldier) was killed straight away, and the neighbor was injured.”

McCann emphasized that a field cannot be considered safe until every piece of explosive debris and every landmine has been removed.

“If there are 50 mines in a field, and somebody finds 49 of them, the field still cannot be used,” he said. “You can only hand back land when you are 100 percent confident that every single mine is gone.

“So, even in places where some people are removing mines, we don’t know if all of them have been cleared, and we’ll have to do clearance again in the future.”

Although the northwest of the Syrian Arab Republic is riddled with unexploded ordnance, locals remain resolute in their determination to stay and rebuild their lives — a decision that is likely to lead to an increase in accidents.

“We think the number of accidents will increase because a lot of people don’t want to leave their displaced communities in Idlib in the winter,” McCann said. “They’re waiting for the weather to improve.”

In the village of Lof near Saraqib, one resident HALO encountered returned to work on his land just hours after the charity’s team had neutralized an unexploded 220mm Uragan rocket. Had it detonated, it would have devastated the village.

“We took the rocket, dug a big hole, and evacuated the whole village,” McCann said. “We used an armored front loader to take it to this demolition site in the countryside.

“By the time we came back to the village, the landowner had started to rebuild his house where the rocket had been. He couldn’t touch it (before), and the rocket had been there probably since 2021.

“But within three or four hours of us removing the rocket, he had started to rebuild.”

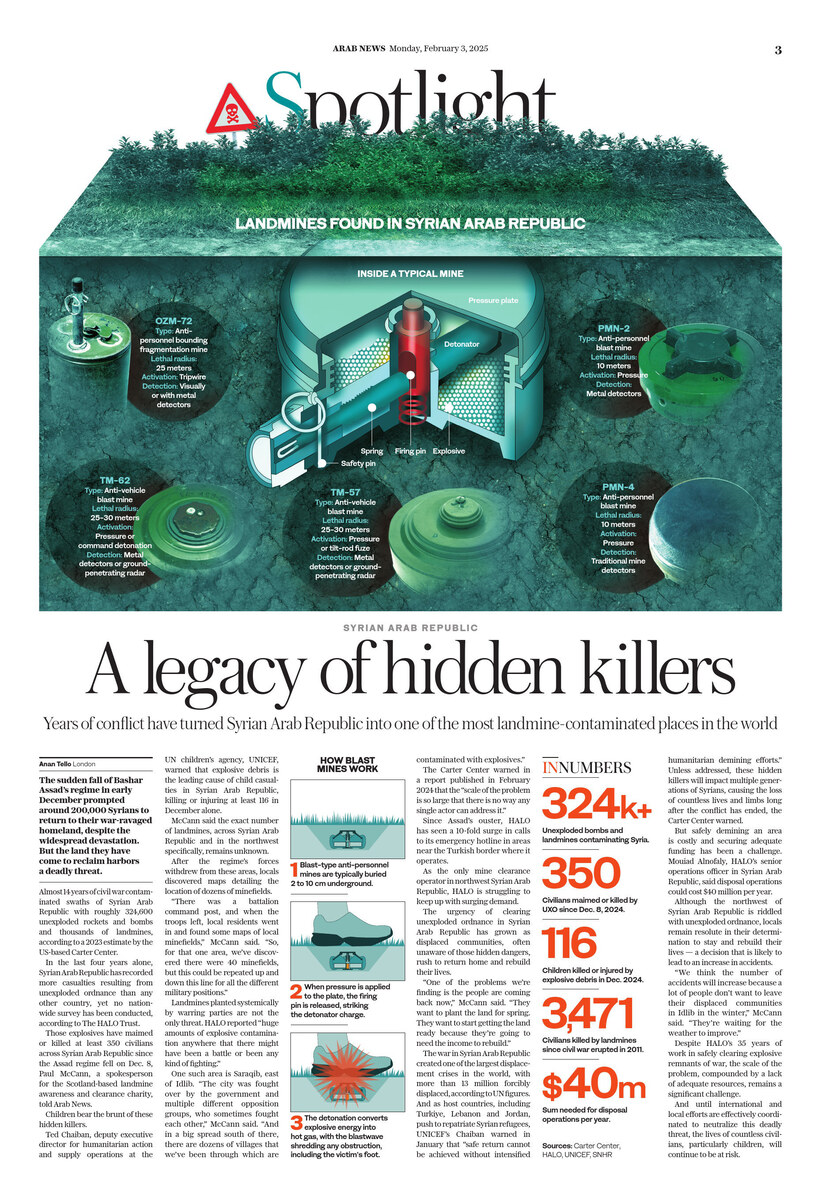

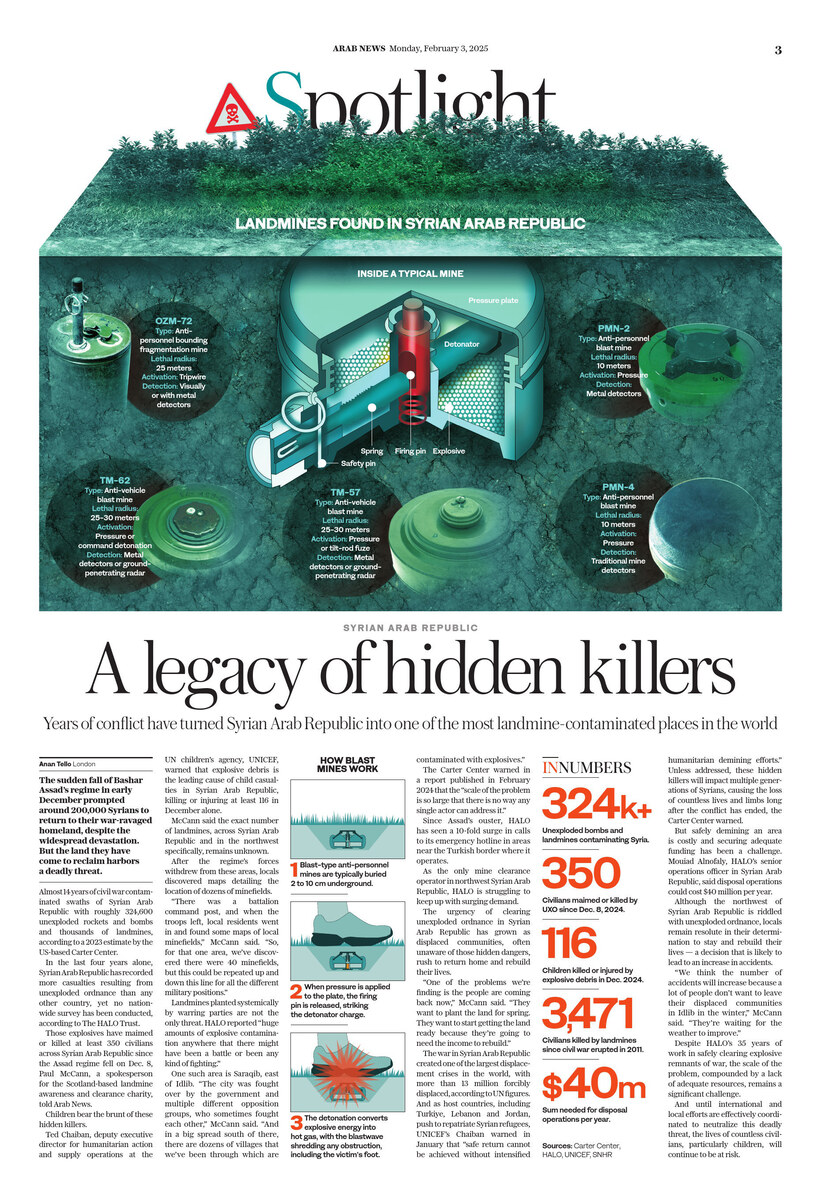

Among the most common unexploded ordnance found in the northwest Syrian Arab Republic are TM-62 Russian anti-tank mines and ShOAB-0.5 cluster bombs.

Despite HALO’s 35 years of work in safely clearing explosive remnants of war, the scale of the problem, compounded by a lack of adequate resources, remains a significant challenge.

“To cover the whole country, there will have to be thousands of Syrians trained and employed by HALO over many years,” said program manager O’Brien.

And until international and local efforts are effectively coordinated to neutralize this deadly threat, the lives of countless civilians, particularly children, will continue to be at risk.