DUBAI: Authorities in Lebanon are imposing new restrictions that could deny thousands of displaced children access to an education. The measures come against a backdrop of mounting hostility toward war-displaced Syrians who currently reside in Lebanon.

The development comes as hostilities on the Lebanon-Israel border show no sign of abating, deepening sectarian divides and compounding the economic and political crises that have kept the country on hold.

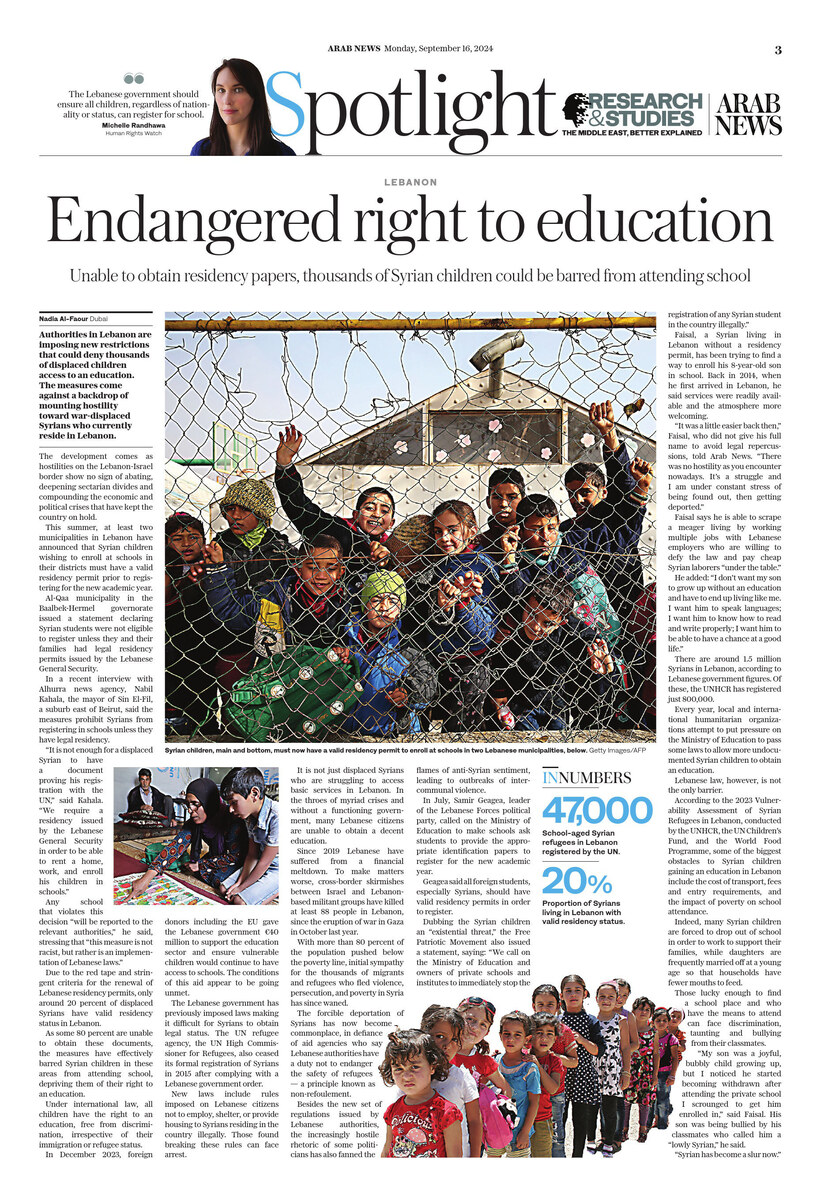

This summer, at least two municipalities in Lebanon have announced that Syrian children wishing to enroll at schools in their districts must have a valid residency permit prior to registering for the new academic year.

In this photo taken in 2016, Syrian refugee children attend class in Lebanon's town of Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley. (AFP/File)

Al-Qaa municipality in the Baalbek-Hermel governorate issued a statement declaring Syrian students were not eligible to register unless they and their families had legal residency permits issued by the Lebanese General Security.

In a recent interview with Alhurra news agency, Nabil Kahala, the mayor of Sin El-Fil, a suburb east of Beirut, said the measures prohibit Syrians from registering in schools unless they have legal residency.

“It is not enough for a displaced Syrian to have a document proving his registration with the UN,” said Kahala. “We require a residency issued by the Lebanese General Security in order to be able to rent a home, work, and enroll his children in schools.”

Any school that violates this decision “will be reported to the relevant authorities,” he said, stressing that “this measure is not racist, but rather is an implementation of Lebanese laws.”

Due to the red tape and stringent criteria for the renewal of Lebanese residency permits, only around 20 percent of displaced Syrians have valid residency status in Lebanon.

As some 80 percent are unable to obtain these documents, the measures have effectively barred Syrian children in these areas from attending school, depriving them of their right to an education.

A stringent Lebanese residency requirement has barred many Syrian children from attending school, depriving them of their right to an education. (AFP)

Under international law, all children have the right to an education, free from discrimination, irrespective of their immigration or refugee status.

In December 2023, foreign donors including the EU gave the Lebanese government 40 million euros to support the education sector and ensure vulnerable children would continue to have access to schools. The conditions of this aid appear to be going unmet.

“The Lebanese government should ensure all children, regardless of nationality or status, can register for school and are not denied the right to an education,” Michelle Randhawa of the Refugee and Migrant Rights Division at Human Rights Watch said in a recent statement.

In an interview with L’Orient-Le Jour on Aug. 13, Lebanese Minister of Education Abbas Halabi said his ministry remained committed to the core principle of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and that all children, regardless of nationality or status, would be registered for school.

A stringent Lebanese residency requirement has barred many Syrian children from attending school, depriving them of their right to an education. (AFP)

The Lebanese government has previously imposed laws making it difficult for Syrians to obtain legal status. The UN refugee agency, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, also ceased its formal registration of Syrians in 2015 after complying with a Lebanese government order.

New laws include rules imposed on Lebanese citizens not to employ, shelter, or provide housing to Syrians residing in the country illegally. Those found breaking these rules can face arrest.

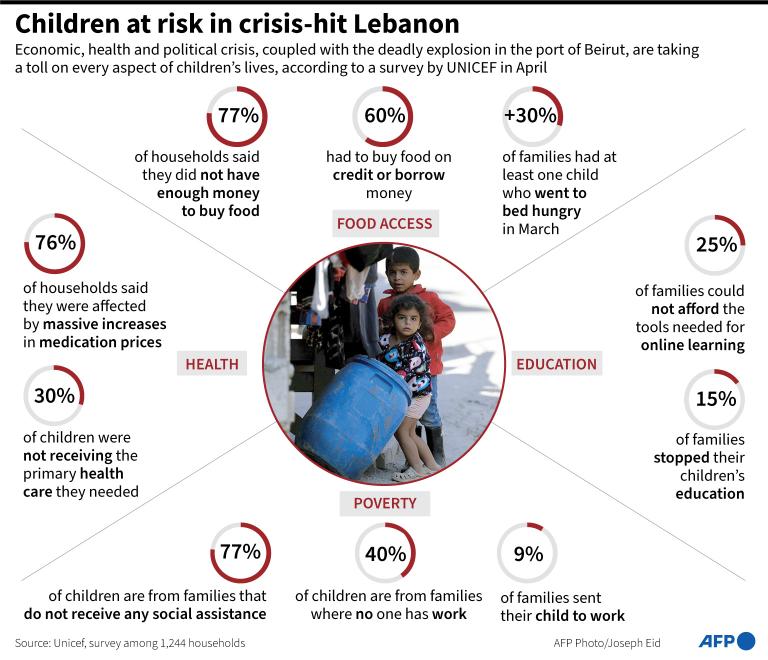

It is not just displaced Syrians who are struggling to access basic services in Lebanon. In the throes of myriad crises and without a functioning government, many Lebanese citizens are unable to obtain a decent education.

Since 2019 Lebanese have suffered from a financial meltdown described by the World Bank as one of the planet’s worst since the 1850s. To make matters worse, cross-border skirmishes between Israel and Lebanon-based militant groups have killed at least 88 people in Lebanon, mostly Hezbollah combatants but also 10 civilians, since the eruption of war in Gaza in October last year.

Only around 20 percent of displaced Syrians have valid residency status in Lebanon, enabling them to attend school. (AFP)

With more than 80 percent of the population pushed below the poverty line, initial sympathy for the thousands of migrants and refugees who fled violence, persecution, and poverty in Syria has since waned.

The forcible deportation of Syrians has now become commonplace, in defiance of aid agencies who say Lebanese authorities have a duty not to endanger the safety of refugees — a principle known as non-refoulement.

Besides the new set of regulations issued by Lebanese authorities, the increasingly hostile rhetoric of some politicians has also fanned the flames of anti-Syrian sentiment, leading to outbreaks of inter-communal violence.

INNUMBERS

• 470,000 School-aged Syrian refugees in Lebanon registered by the UN.

• 20% Proportion of Syrians living in Lebanon with valid residency status.

In July, Samir Geagea, leader of the Lebanese Forces political party, called on the Ministry of Education to make schools ask students to provide the appropriate identification papers to register for the new academic year.

Geagea said all foreign students, especially Syrians, should have valid residency permits in order to register.

Dubbing the Syrian children an “existential threat,” the Free Patriotic Movement also issued a statement, saying: “We call on the Ministry of Education and owners of private schools and institutes to immediately stop the registration of any Syrian student in the country illegally.”

Faisal, a Syrian living in Lebanon without a residency permit, has been trying to find a way to enroll his 8-year-old son at school. Back in 2014, when he first arrived in Lebanon, he said services were readily available and the atmosphere more welcoming.

Syrian children run amidst snow in the Syrian refugees camp of al-Hilal in the village of al-Taybeh near Baalbek in Lebanon's Bekaa valley on January 20, 2022. (AFP)

“It was a little easier back then,” Faisal, who did not give his full name to avoid legal repercussions, told Arab News. “There was no hostility as you encounter nowadays. It’s a struggle and I am under constant stress of being found out, then getting deported.”

Faisal says he is able to scrape a meager living by working multiple jobs with Lebanese employers who are willing to defy the law and pay cheap Syrian laborers “under the table.”

He added: “I don’t want my son to grow up without an education and have to end up living like me. I want him to speak languages; I want him to know how to read and write properly; I want him to be able to have a chance at a good life.”

There are around 1.5 million Syrians in Lebanon, according to Lebanese government figures. Of these, the UNHCR has registered just 800,000.

Every year, local and international humanitarian organizations attempt to put pressure on the Ministry of Education to pass some laws to allow more undocumented Syrian children to obtain an education.

Lebanese law, however, is not the only barrier.

According to the 2023 Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon, conducted by the UNHCR, the UN Children’s Fund, and the World Food Programme, some of the biggest obstacles to Syrian children gaining an education in Lebanon include the cost of transport, fees and entry requirements, and the impact of poverty on school attendance.

Syrian refugee children play while helping tend to their family's sheep at a camp in the agricultural plain of the village of Miniara, in Lebanon's northern Akkar region, near the border with Syria, on May 20, 2024. (AFP)

Indeed, many Syrian children are forced to drop out of school in order to work to support their families, while daughters are frequently married off at a young age so that households have fewer mouths to feed.

Those lucky enough to find a school place and who have the means to attend can face discrimination, taunting and bullying from their classmates.

“My son was a joyful, bubbly child growing up, but I noticed he started becoming withdrawn after attending the private school I scrounged to get him enrolled in,” said Faisal. His son was being bullied by his classmates who called him a “lowly Syrian,” he said.

“Syrian has become a slur now.”